Flying Officer Donald Charles Gundry, the son of Harris Musgrove Gundry and Ethel Purland Gundry (nee Windley), was born at Toowoomba in Queensland on 26th December 1916. He was educated at the Toowoomba Grammar School. At the age of 25 years he was enrolled in the Reserve of the Royal Australian Air Force in Adelaide on 12th January 1942 after swearing the statutory oath of allegiance. At the time of his enrolment he was married, employed as a Clerk and residing with his wife and daughter at 36 Sturt Street, St Leonards, South Australia. At the age of 25 years and 6 months he was enlisted in the Reserve of the R.A.A.F. at No. 5 Recruiting Centre in Adelaide on 18th July 1942 after giving an undertaking that he would serve for the duration of the war and an additional twelve months. His description was that he was 6 feet 1 inch in height and weighed 196 pounds. He had a dark complexion, brown eyes and dark hair. He stated that he was of the Church of Christ religion. He gave his next of kin as his wife, Mrs Quetta Joyce Gundry, residing at 36 Sturt Street, St Leonards, Adelaide. He also gave his parents, Mr and Mrs H.M. Gundry, residing at 6 Eleanor Street in Toowoomba, as persons to be notified in the event of injury or death.

Flying Officer Donald Gundry was allotted the service number of 417833. He joined No. 4 Initial Training School at Mt Brecken, Victor Harbour, South Australia, on 18th July 1942 where he was trained in military discipline and the basics of military aviation. After completing the training, he was selected for training as a Pilot. He joined No. 1 Elementary Flying Training School at Parafield in South Australia on 3rd November 1942 where he underwent training on basic single-engined trainer aircraft. He joined No. 6 Service Flying Training School at Mallala in South Australia where he received advanced flying training on single and multi-engined aircraft. After graduating at Mallala he was awarded the Pilot Qualification Badge on 4th May 1943 and promoted to the rank of Temporary Sergeant on 6th May 1943. He joined No. 4 Embarkation Depot at Mitcham in South Australia on 13th May 1943 and to No. 2 Embarkation Depot at Bradfield Park in Sydney on 18th May 1943 to prepare for movement overseas on attachment to the Royal Air Force.

Flying Officer Donald Gundry embarked from Sydney in Australia on 25th May 1943 and he disembarked in England on 7th July 1943. On the following day he joined No. 11 Personnel Despatch & Reception Centre at Bournemouth. He joined No. 15 (Pilot) Advanced Flying Unit at Royal Air Force Station Babdown Farm on 17th August 1943. He completed a course of training at No. 1 Beam Approach Training School during the period 28th September until 5th October 1943. He was promoted to the rank of Temporary Flight Sergeant on 6th November 1943. He joined No. 27 Operational Training Unit at Royal Air Force Station Lichfield on 16th November 1943 where he trained for night bombing using Vickers Wellington aircraft. He was commissioned as a Flying Officer on 17th February 1944. He joined No. 51 Base in Lincolnshire on 5th April 1944 for conversion training. He joined No. 463 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force Station Waddington for operational duty on 12th July 1944.

Australian War Memorial photograph P10504.005

No. 30 course at No. 4 Initial Training School. Flying Officer Donald Charles Gundry is seventh from the left in the back row.

Flying Officer Donald Gundry was the pilot and captain of a No. 463 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force Avro Lancaster bomber LM.589 that went missing during air operations on 25th July 1944, presumed to have been due to enemy action. The aircraft was detailed to attack a target at St Cyr, Amar, Paris. The aircraft was hit by flak when it was approaching the target and again over the target area. The interior of the aircraft and the starboard inner engine were set on fire and at 8000 feet Flying Officer Gundry instructed the crew to abandon the aircraft. Five crew members were seen to parachute from the aircraft as it dived out of control. A report from one of the survivors suggested that Flying Officer Donald Gundry and another member of the crew were unable to exit the doomed aircraft and were killed. At the time of his death Donald Gundry was 27 years of age.

After hostilities had ceased in the area where the aircraft had crashed, No. 1 Section of the Missing Research & Enquiry Service submitted the following report on their investigation into the crash of Flying Officer Gundry’s Wellington aircraft on 26th June 1945:

An investigation was carried out on 22nd June 1945 in the area indicated in para 3 of your P.42729/44/p.4/503.S. I made extensive enquiries in this area but without result. I continued in a north-westerly direction along the main Noisy-le-Roi Mantes Gassicourt road and from there along the Gourney road making enquiries at Mairie and Gendermerie. Eventually at the village of Aincourt – 7 miles north of Mantes I was informed that a British bomber had crashed near the village of Chaussy on 25th July 1944. At Chaussy I spoke with several people including the Mayor who informed me that this aircraft crashed at 20.10 hours on 25th July 1944. The machine was diving towards the village with the starboard outer engine in flames, but at the last moment the aircraft banked steeply to port and crashed just outside the village. Five of the crew were seen to bail out and it was known that four were taken prisoner, one of whom broke his leg on landing and was taken away to a hospital in Paris. The remains of two bodies were removed from the wreckage, put in a box and buried at Omerville. The Gendarmes handed me the enclosed photos which were found in the wreckage. On the back of one photo the following is written: “833 Flight Sergeant Gundry” who was the pilot of Lancaster LM.589. A flying helmet was also found with the name “Davidson” on the inside. The villagers assumed that Davidson was one of the members who perished, so I informed them that he had escaped and returned to the U.K. Several other personal belongings and sums of money were taken by the Germans. At Omerville I was shown the grave containing the remains of two airmen (evidently Flying Officer Gundry and Flight Sergeant Scheldt) who crashed at Chaussy. The cross is marked in German as follows: – 2 Unbekannte Englische Flieger abgeschossen a.m. 25/7/44. Uber Chaussy. There are three other graves of Allied airmen alongside, all four being in a large plot of their own about 100 yards behind the Mairie. A small monument has been erected in front of the graves with the following inscription on a marble slab: – Reconnaissance. A nos alliés Libérateurs Morts au champ d’honneur Offert par les combattants d’Omerville 1914-1918 1939-1940. The enclosed photo was taken at the unveiling ceremony. The grave referred to in this report is the first on the left. May we arrange to have the names of Flying Officer Gundry and Flight Sergeant Scheldt inscribed on the cross? Signed J.D. Robertshaw, Squadron Leader.

Donald Gundry’s headstone in the Omerville Communal Cemetery contains the family inscription “Greater Love Hath No Man Than This. Ever Remembered”. Donald Gundry’s name is commemorated on Panel No. 109 at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra and locally on the Toowoomba Grammar School World War 2 Honour Board.

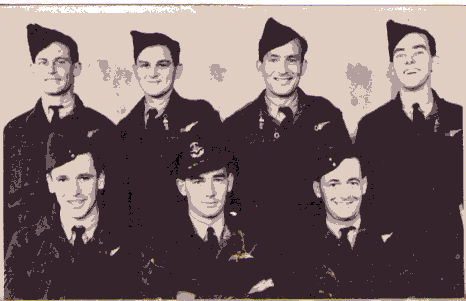

The following photograph of Flying Officer Gundry and his crew appeared in “The South Australia Advertiser” on 6th October 1944 and can be found on page 10 of Flight Sergeant John Barnes Sincock’s military record.

Flying Officer Gundry’s photograph and the following text were published in the Toowoomba Chronicle on 25th July 1945:

“AIR BOARD’S LETTER – FLYING OFFICER D. GUNDRY – NAVIGATOR’S PRAISE”. – It is 12 months today since Flying Officer Donald Charles Gundry, eldest son of Mr and Mrs H.M. Gundry, 6 Eleanor Street, Toowoomba, and husband of Mrs D.C. Gundry, 4 James Street, was reported missing in operations in France. Mrs D.C. Gundry, in a letter received this month from the Air Board, was advised that the only information received from the German authorities was that three were taken prisoner. The Germans did not report that two other members of the crew were injured and left in Paris on its recapture. These details were learnt only from the members themselves. The Germans did not notify the International Red Cross Committee, Geneva, that two members of the crew had lost their lives; in fact, in reply to a special inquiry made concerning Flying Officer Gundry, the Germans advised the International Red Cross Committee that they had no news of him. The letter added: “In view of the fact that a long period of time had now elapsed without any news of your husband or Flight Sergeant Scheldt, the regrettable conclusion must be reached that they have both lost their lives. It has not been possible to presume their deaths earlier because of the lack of definite evidence”.

Flight Sergeant J.B. Sincock, in a report to Group Captain D.W.F. Bonham-Carter, Officer Commanding, Royal Air Force Station, Waddington, Lincolnshire, stated inter alia: “On the evening of July 25, 1944, I was the navigator of Lancaster Joy (captained by Flying Officer Gundry), which was detailed to attack a target at St. Cyr, France, in an operation shortly before nightfall. The aircraft’s height was 8000 feet. On the run-up to the target the flak was very heavy and accurate. Before reaching the target the aircraft was hit heavily and vibrated considerably. The skipper kept perfect control, flying through further flak. Two or three seconds after “Bombs gone” the aircraft was hit again. “I should like to comment on the skill, bulldog determination, and gallantry of our skipper. This was by no means the first occasion on which we had seen them. His pluck and skill were always evident and he was always cool in emergencies. On July 25, he was the same courageous, determined skipper he had always been. When we were hit on our bombing run it was our bombs which came first. With them on the way to the target the safety of the other aircraft in the formation became his first thought, and to make sure that no other aircraft was endangered by ours he lost precious height. With that danger past, and only then, he thought of his own aircraft and crew. He held on beyond all the bounds of duty and courage, in my opinion. He had an engine on fire. He heard of another fire in the fuselage, and he said, “Fight it with extinguishers”. He thought to keep his aircraft flying and his crew together. When he finally gave the order to jump he left himself little or no time to get out. His own life came last, and he had everything to live for. It was an honour to fly with him, and a still greater honour to be his friend”.

The following three airgraphs sent to his family by Flight Sergeant John Sincock give an added insight into the events that led up to Don Gundry’s death:

Airgraph 1.

September 6th, 1944: My dear family. First of all a summary of the events of the past six weeks. July 25th. Our aircraft was hit five times by flak near Paris and with the aircraft on fire in two places it became necessary to take to our parachutes. It was our sixth operational flight. The aircraft seemed to be going out of control when I got out. I remember having to fight to get out of the escape hatch, but I don’t remember opening my “chute”, the descent, or the landing.

The next thing I do remember is being pulled out of a truck by German soldiers who, at the same time were pulling things out of my pockets. A doctor pronounced my right leg broken and my left one dislocated. For two days I was kept there and then taken to Paris to the Luftwaffe Hospital there, making the journey with three other uninjured members of the crew who were being sent as prisoners to Germany. Saw one other member of the crew who had been hit by flak. He is now in the ward of an English Hospital with me.

What happened to Don and Vern I do not know for certain, but I fear they didn’t get out. In a few days I will be writing their people to tell them as much as I can. Was well treated in Luftwaffe Hospital from July 25th, until the Germans left us behind in the hands of French Doctors and Staff, when leaving Paris on August 18th. – Jan’s birthday.

High adventure for 8 days until the armies marched in. Was then evacuated to England by ambulance and aircraft. Couldn’t send you all cables because I arrived in England with a farthing only. Germans took the rest. I broke my right leg – just a simple fracture. However, I will be in bed for another three weeks or so before I begin walking and strengthening my muscles and ligaments. More to come. Love to all, John.

Airgraph 2.

September 7th, 1944. My dear Family. Here goes on the detailed description of the last six weeks. It begins on July 25th when we took part in a daylight attack on a French target.

It was somewhere about eight o’clock at night which over here, then, was broad daylight. It was our sixth operation but our first daylight one and it was the most magnificent sight I had ever seen. On all sides were silver wings of high-powered aircraft riding a carpet of enemy flak on their run in to the target and then the bombs were falling, miraculously, it seemed, missing the aircraft a little lower down. And then a great column of smoke and debris was rising and something else which had contributed to the strength of the German war machine just didn’t exist anymore. A magnificent sight, even more inspiring than the sight I had many times in the closing stages of my training – watching the great swarm of bombers rise at dusk over England like mosquitos over a swamp. But I’m getting ahead of myself. On the run into the target we were hit twice. First of all flak thudded into the bombs in the bomb bays below us. A few seconds later another burst came through the floor of the aircraft behind me and then our bombs were going and we turned for home. Only a few seconds later another burst got us and the mid-upper gunner (Nevin Davidson) sang out that he had been hit. Things happened pretty fast from there. Continuing in the next airgraph. John.

Airgraph 3.

September 8th, 1944. My dear Family. After Nevin was hit I went off the intercom to go down and get him out of the turret. I had just got Nevin out when I was joined by Vern Scheldt who had come down to help. At this stage I noticed that fire had broken out near Vern’s position, so left Nevin in Vern’s care and tackled the fire with an extinguisher informing Don (the pilot) before doing so. Extinguisher had no effect so told Don so, and he gave the order to jump. I didn’t know at the time, because I’d been off the intercom, that one of our starboard engines was well alight, also I saw the bomb aimer (Fallon) and engineer (Wadsworth) going and saw Vern and Nevin pass behind the rear turret on their way to the rear escape hatch while I was doing one or two little jobs I had to do before jumping. Then I put Don’s “chute” on him, squeezed his arm and bailed out the front hatch.

I don’t remember opening my “chute”, the descent, or the landing, but I have a vague recollection of having a struggle to get out. The next thing I remember is when I came round, I must have been unconscious almost from the moment I left the “plane”. When I came round I was being pulled out of a German truck, and the Germans were taking things out of my pockets and trying to make me walk. It took a bit of thinking to realise where I was and then I sang out in German that my leg was broken. They then carried me into a building where a doctor had a look at me. More to come. John

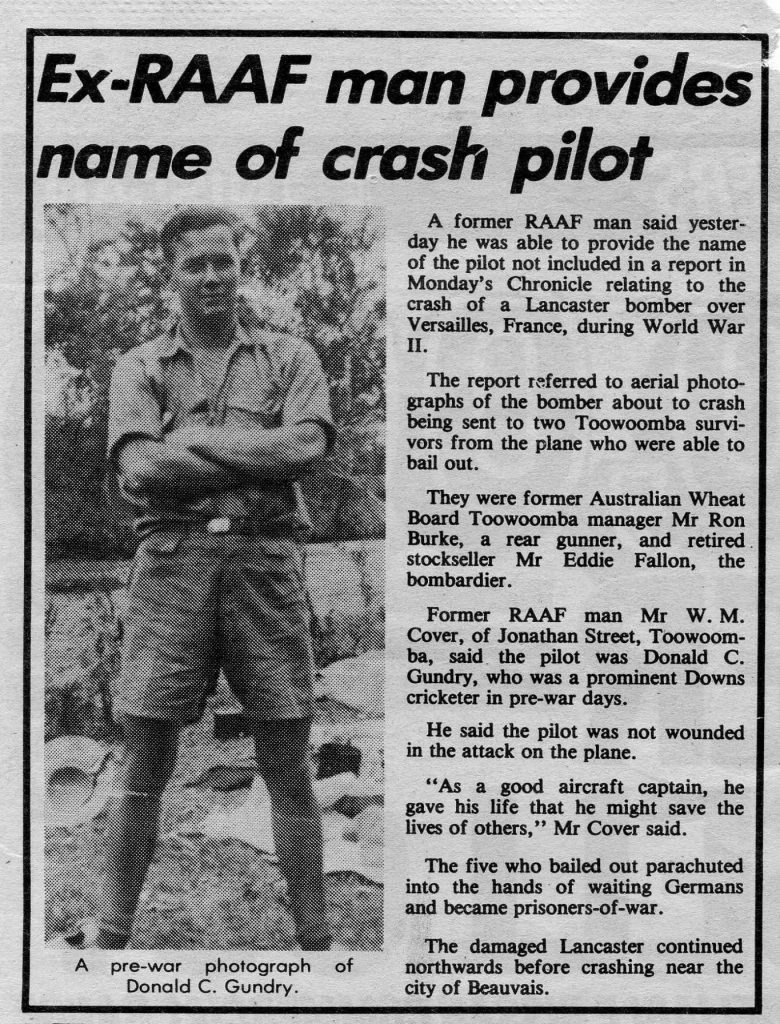

The following newspaper report that included a photograph of Donald Gundry, published in the Toowoomba Chronicle, was recently sent to me by Eric Salzman and Jean Gundry:

EX-RAAF MAN PROVIDES NAME OF CRASH PILOT – A former RAAF man said yesterday he was able to provide the name of the pilot not included in a report in Monday’s Chronicle relating to the crash of a Lancaster bomber over Versailles, France, during World War 2.

The report referred to aerial photographs of the bomber about to crash being sent to two Toowoomba survivors from the plane who were able to bail out. They were former Australian Wheat Board Toowoomba manager, Mr Ron Burke, a rear gunner, and retired stock seller Mr Eddie Fallon, the bombardier. Former RAAF man Mr W.M. Cover, of Jonathon Street, Toowoomba, said the pilot was Donald C. Gundry, who was a prominent Downs cricketer in pre-war days.

He said the pilot was not wounded in the attack on the plane. “As a good aircraft captain, he gave his life that he might save the lives of others,” Mr Cover said. The five who bailed out parachuted into the hands of waiting Germans and became prisoners of war. The damaged Lancaster continued northwards before crashing near the city of Beauvais.

It would have been very unusual for three members of the crew of a Lancaster to come from the same city. It would suggest strongly that Donald Gundry would have been instrumental in selecting Eddie Fallon and Flight Sergeant Burke as members of his crew.

Acts of bravery such as that displayed by Don Gundry were worthy of a bravery award and there are many instances of similar acts of bravery as shown by Flying Officer Donald Gundry being awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross. However, as he did not survive after demonstrating such a heroic deed, regulations only allowed the posthumous award of a Victoria Cross or a Mention in Dispatches. It is possible that a recommendation to recognize his bravery failed to eventuate as a result of the time that elapsed before knowledge of his heroic deed became known near the end of the war when his crewmates were repatriated from captivity. As Don Gundry was the only commissioned officer in the crew he would have been unable to be recommended for a Victoria Cross as acts of bravery warranting the award of a VC had to be witnessed by an officer.

Australian War Memorial photograph P031127.001

Flying Officer Donald Gundry (centre) and crew in front of a No. 463 Squadron Vickers Wellington aircraft.

Australian War Memorial photograph P03127.002

Flying Officer Donald Gundry’s Lancaster “Y for Yorker” photographed flying low over the town of St Cyr, France, just before it crashed. The aircraft’s starboard inner engine is on fire and the remaining engines are losing fuel.

Toowoomba Grammar School archive records show that he enrolled as a day student on 28th January 1931 and that he left the School on 8th December 1933. His parent was shown as Mr Harris Musgrove Gundry, a Farmer/Fencing Contractor residing at “Columboola”, Toowoomba. He passed eight subjects in the Junior examination in 1932. He represented the School in Cricket and Tennis and also represented Toowoomba in cricket. After leaving school he joined the Past Grammar Cricket Club. He played a number of games with Toowoomba in intercity games, and showed much promise as a left-hand fast bowler. He worked a few years with Rhinholdt Engineering as a Cost Clerk around Toowoomba and on the Western Line. He married Miss Quetta Burge in 1940 and moved to Menindie in New South Wales. They have one child, Jenifer Lenore Gundry, who was born on 19th December 1940. He then moved to Adelaide working for the Vacuum Oil Company

The following was published in the Courier Mail newspaper on 25th April 2002:

On July 25, 1944, my father was a 22 year old air gunner on a burning R.A.A.F. Lancaster bomber (flying over German-occupied France. With its crew of seven, the Lancaster Y for Yorker was one of 100 aircraft on a daylight raid to bomb the railway marshalling roads at St Cyr, west of Paris. As they approached the target, the lumbering Lancasters flew into a carpet of flak (anti-aircraft fire). Y for Yorkers’ crew saw the plane on their left hit, then the plane to the right. “Give ‘em time to get another round in the breech, and it’ll be our turn,” quipped the pilot, Flying Officer Don Gundry, 27, of Toowoomba, over the intercom – just as another anti-aircraft shell struck the fuselage.

As Don struggled to control the plane, it was hit again, and then twice more. One piece of shrapnel came up through the mid-upper gun turret where Dad was sitting and smashed the bone on his lower left leg, leaving it hanging by muscle and flesh. Luckily, the bomb-aimer was unharmed and managed to get the bombs away. By then there was fire in the fuselage, fire on the starboard wing, and two of the four engines were gone – so Don ordered the crew to bail out. He held the bomber steady as the rest of them scrambled for their parachutes and headed for the escape hatches.

Wounded in the leg, Dad was unable to move from the gun turret. The wireless operator, Flight Sergeant Vernon Scheldt, 22, from Nanango, came to help. Grabbing Dad by the chest, Vernon hauled him down from the turret, helped him into his parachute, dragged him to the hatch and pushed him out behind the four other crewmen. But it was too late for Vernon. As Dad parachuted away, the fire took hold and Vernon was trapped without a parachute. Don may have realised this, because as the burning Lancaster gradually lost height he stayed aboard and held it steady, possibly hoping to “pancake” and give Vernon a chance to survive. But to no avail. Y for Yorker crashed into the countryside near Beauvais, north of Paris. Both Don and Vernon were killed.

My father landed in a park in Paris, was taken prisoner by the Germans, treated very well in a prison hospital, liberated by the Americans and repatriated to England and then home. He recovered (apart from a life-long limp) raised a family and had a full life. For half a century the selflessness of Don Gundry and Vernon Scheldt had rattled around in my family’s collective memory. I was revived when Dad received a letter from a fellow Y For Yorker crewman Flight Sergeant Frank Wadsworth, of England, in 1987. And the story was told again by my uncle – Dad’s brother – in a eulogy at Dad’s funeral last year. He reminded us that 56 years of Dad’s life were a gift from two selfless men. “I’d like to stand beside their graves, and leave a few flowers there to remember what they did,” my uncle said.

A month later, my wife, son and I went to find those graves. Thanks to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s website, we know that Don Gundry and Vernon Scheldt were buried at Omerville, north-west of Paris. Omerville is a charming old village of 100 or so stone houses tucked around an ancient, weathered church and an imposing, twisted chateau. There also was a school. Our taxi driver took us down a narrow lane and there, near an ornate gate in a high stone wall, was a comforting sight – in English: “Commonwealth War Graves”. We pushed open the gate to the village cemetery. Against a far wall, beyond the lichen-covered graves of long-deceased Omervillians, was a row of six distinctive, sandstone military headstones – clean and well-tended after 50 years. The graves of Vernon Scheldt and Don Gundry were side by side. I stood with my son, 22 – the same age Dad and Vernon were in 1944. The two young men buried at our feet had given my father and through him, my son and I, a chance at living. The other graves contained the remains of British, Canadian and South African flyers. Vernon’s epitaph read: HIS DUTY FEARLESSLY AND NOBLY DONE: and Don’s: GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS. In my pocket I had two small rocks I had brought from Brisbane. I placed one on each grave among the gravel near the two headstones. I expect they are still there.

DON GUNDRY’S CREW

Don Gundry, 417833 pilot, next of kin Mrs Quetta Gundry (wife) of 4 James Street, Toowoomba.

Flight Sergeant J.B. Sincock 417899, navigator, next of kin Mrs J.B. Sincock (wife) c/- Mrs T.R. Owen, 23 Seafield Avenue, Ingswood, South Australia. Father Mr J. Sincock 112 Cambridge Terrace, Malvern, South Australia.

Flight Sergeant E.J. Fallon, 426565 Air Bomber, nest of kin Mrs A. Fallon (wife), 211 James Street Toowoomba.

Flight Sergeant V.J. Scheldt, 426691, Wireless Operator/Air Gunner, next of kin Mr J.P. Scheldt, (father)Kanyan, North Coast Line.

Sergeant H.M. Davidson 426794, Mid Upper Air Gunner, next of kin Mr Davidson (father) Shirley Street, Byron Bay, New South Wales.

Flight Sergeant F. Burke, 426527. Rear Air Gunner, next of kin, Mrs E. Burke, 9 McCarthy Street, Toowoomba, Queensland.

Sergeant Wadsworth, Royal Air Force, Flight Engineer, No details available

General view of Chaussy (Photograph by Zivax) that was avoided by Flying Officer Donald Gundry

Memorial outside Chaussy

“TO THE ALLIED PILOTS FALLEN HERE

…

FOR THE FREEDOM OF THE COUNTRY”